Karnak: The Stone Forest of the Pharaohs

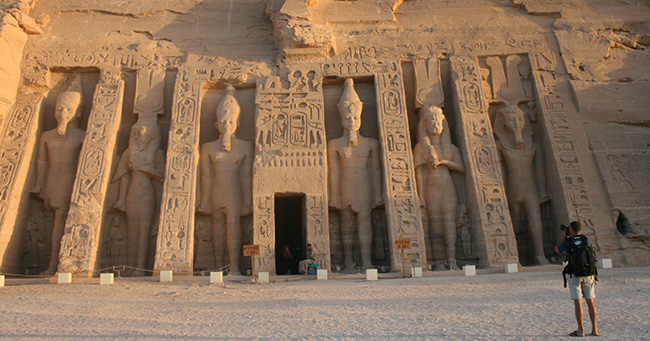

The Karnak Temple Complex, situated on the east bank of the Nile in Luxor, is not merely an archaeological site; it is an expansive historical archive carved in stone. For over 1,500 years, it stood as the religious epicenter of Ancient Egypt.

Covering more than 200 acres, it remains the largest religious building ever constructed. To understand Karnak is to understand the evolution of the Egyptian Empire—from its rise in the Middle Kingdom to its grand imperial peak and its eventual Hellenistic transformation.

The Theological Foundation: Why Karnak?

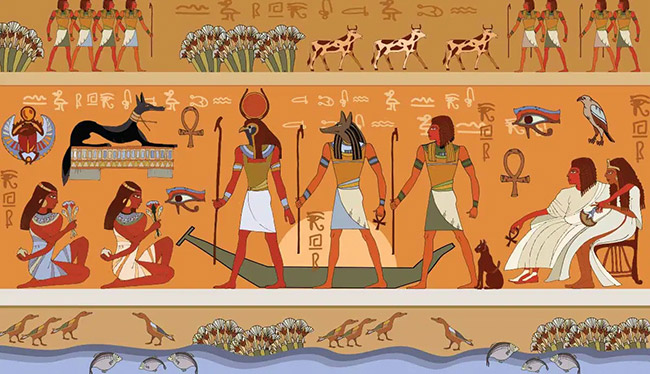

In the ancient tongue, Karnak was called Ipet-isut, translated as “The Most Select of Places.” While Egypt had many gods, the New Kingdom elevated Amun-Ra to the status of a “King of Gods.” Karnak was considered his earthly residence.

The complex was designed as a “cosmic machine” where the gods lived, and the Pharaohs acted as the bridge between the divine and the mortal. The temple’s layout was a physical representation of the Egyptian creation myth. The ground rose towards the sanctuary, symbolizing the “Primeval Mound” emerging from the waters of chaos.

Chronological Expansion: A Layered History

One of the most fascinating aspects for historians is that Karnak was never “finished.” Each Pharaoh sought to immortalize their devotion by adding something grander than their predecessor.

The Middle Kingdom Seeds (2000 – 1700 BCE)

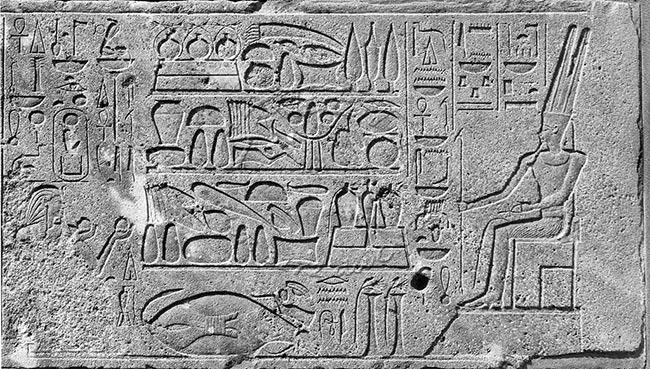

The earliest structures date back to the 11th and 12th Dynasties. Senusret I built a modest limestone temple here. Though much of it was later dismantled, archaeologists recovered the White Chapel, which features some of the finest high-relief carvings in Egyptian history.

The New Kingdom: The Imperial Explosion (1550 – 1070 BCE)

This was the era of the warrior-kings and the great builders.

- Thutmose I: He was the first to significantly expand the core of the temple, erecting two massive pylons and two obelisks.

- Queen Hatshepsut: Her contribution was both religious and political. She erected two of the largest obelisks in the world at the time. One still stands, a 300-ton granite monolith that symbolizes her power.

- Thutmose III: After Hatshepsut, he built the Ach-menu or the “Festival Hall.” It is unique for its “tent-pole” columns, designed to resemble the military tents he used during his many successful campaigns in Asia.

The Great Hypostyle Hall: An Architectural Marvel

If Karnak is a crown, the Great Hypostyle Hall is its brightest jewel. Commenced by Amenhotep III, but largely executed by Seti I and completed by Ramesses II, this hall is an engineering feat that defies its era.

- The Forest of Pillars: It contains 134 massive columns. The 12 central columns are 21 meters high, with capitals shaped like open papyrus flowers.

- Symbolism: The hall represents a papyrus marsh at the dawn of creation. The ceiling was once painted blue with golden stars, representing the night sky.

- The Walls of War: The exterior walls are covered in detailed reliefs. On the north wall, Seti I is seen battling the Hittites and Libyans; on the south, Ramesses II commemorates the Battle of Kadesh. For historians, these are essential primary sources for ancient military history.

The Political Turmoil: The Amarna Period

A critical chapter in Karnak’s history is the Amarna Revolution. When the “heretic king” Akhenaten ascended the throne, he abandoned Amun in favor of the sun-disk, Aten. He built a massive temple to Aten at Karnak, but located it outside the traditional boundaries to signal his break from the priesthood.

After his death, his successors—specifically Horemheb and the early Ramesside kings—systematically dismantled his temples. The stones were used as “filler” inside the massive pylons we see today. This act of damnatio memoriae (erasing someone from history) inadvertently preserved thousands of Akhenaten’s decorated blocks, known as talatat, which modern archaeologists have used to reconstruct his lost history.

Rituals and Festivals: The Pulse of the People

Karnak was the stage for the Opet Festival, the most important event in the Theban calendar. During the season of the Nile flood, the statues of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu were placed on ceremonial barques (boats) and carried from Karnak to Luxor Temple.

This wasn’t just a party; it was a political necessity. During the festival, the Pharaoh’s “Ka” (divine spirit) was ritually renewed. It proved to the people that the king still held the favor of the gods, ensuring the fertility of the land and the stability of the state.

Detailed Architectural Breakdown

The Ten Pylons

Karnak is structured around two main axes. The North-South axis points toward Luxor Temple, while the East-West axis points toward the Nile.

- Pylon I: The main entrance, built by the 30th Dynasty. It remains unfinished, providing a rare look at how ancient Egyptians used mud-brick ramps to lift massive stones.

- Pylon III: Built by Amenhotep III. This pylon is a “treasure chest” for archaeologists, as it contained hundreds of blocks from older, dismantled shrines.

- Pylon VII-X: These define the southern approach and were primarily built by Thutmose III and Horemheb.

The Sacred Lake

Measuring 120 by 77 meters, this lake was fed by Nile groundwater. Here, the “Pure Priests” would bathe four times a day to maintain ritual purity. Nearby, the Colossal Scarab of Amenhotep III stands—a symbol of the sun-god Khepri and eternal rebirth.

The Late Period and the Ptolemaic Influence

As the native Egyptian dynasties weakened, foreign rulers took over, yet they all recognized Karnak’s importance.

- The Nubian Kings (25th Dynasty): King Taharqa built a massive kiosk in the first courtyard with 21-meter high columns, showing the Kushite devotion to Amun.

- The Ptolemies: These Greek rulers added massive gateways and small chapels. They were careful to depict themselves in the traditional Egyptian Pharaoh’s garb, offering sacrifices to Amun to avoid rebellion from the powerful Theban priesthood.

Archaeological Discovery: The Cachette of 1903

One of the most significant events in modern archaeology happened at Karnak. In 1903, Georges Legrain discovered a pit in the courtyard of the Seventh Pylon. Inside were nearly 800 stone statues and 17,000 bronzes.

Why were they there? Historians believe that over the centuries, the temple became cluttered with “votive offerings” (statues left by priests and nobles). When space ran out, the priests gathered the older statues and buried them in a sacred “cachette.” This single discovery provided the Egyptian Museum in Cairo with its largest collection of statuary.

Preservation and Modern Significance

Today, Karnak is a UNESCO World Heritage site. It faces modern threats like rising groundwater and salt erosion, which eat away at the sandstone foundations. International teams, including the Franco-Egyptian Center (CFEETK), work year-round to conserve the carvings.

For the modern visitor, the Sound and Light Show offers a dramatic retelling of this history, but for the historian, the true magic lies in the silence between the pillars, where the names of kings like Ramesses, Seti, and Thutmose still echo.

Quick Historical Reference Table

| Era | Primary Builders | Key Features |

| Middle Kingdom | Senusret I | White Chapel, Core Amun Sanctuary |

| Early New Kingdom | Thutmose I, Hatshepsut | Obelisks, Pylons IV and V |

| Peak New Kingdom | Seti I, Ramesses II | Great Hypostyle Hall, War Reliefs |

| Amarna Period | Akhenaten | Temple of the Aten (later destroyed) |

| Late Period | Taharqa, Shoshenq I | Kiosk of Taharqa, Bubastite Portal |

| Greco-Roman | Ptolemy III, IV | Massive Pylon Gateways, Small Chapels |

The Temple of Karnak is not just a relic of a dead religion; it is a monument to human persistence. It survived earthquakes, religious revolutions, foreign invasions, and the passage of three millennia. It remains a testament to a civilization that did not just build for the present, but for eternity.

Walking through its halls, one doesn’t just see ruins; one sees the very foundation of human architectural and spiritual history. It is, and will always be, the “Most Select of Places.”

References

Legrain, Georges (1903). The Karnak Cachette.

Blyth, Elizabeth (2006). Karnak: Evolution of a Temple. Routledge.

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Digital Karnak Project.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Ancient Thebes with its Necropolis.

Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson.