The Epic Evolution and Engineering of Egypt’s Pyramids

The pyramids of Egypt are more than just piles of stone; they are the architectural manifestation of a civilization’s obsession with eternity. Standing as the only surviving Wonder of the Ancient World, the Great Pyramid of Giza continues to baffle modern engineers and historians alike. To understand how these structures came to be, we must look at a timeline of trial, error, and ultimate triumph.

1. The Pre-Pyramid Era: The Mastaba (c. 3100–2700 BCE)

Before the first stone was ever stacked into a triangle, the elite of Early Dynastic Egypt were buried in Mastabas. Derived from the Arabic word for “bench,” a mastaba was a rectangular, flat-roofed structure made of sun-dried mud bricks.

While the burial chamber was located deep underground, the mastaba above served as a chapel for offerings. The transition from mud-brick mastabas to stone pyramids wasn’t just an aesthetic choice; it was a shift toward “immortality through durability.”

2. The Birth of Stone Architecture: Djoser’s Step Pyramid

Around 2630 BCE, a brilliant official named Imhotep—the world’s first named architect—designed a tomb for King Djoser at Saqqara. Imhotep’s innovation was simple but revolutionary: he stacked six mastabas on top of one another, each smaller than the last.

- Height: 62 meters.

- Material: Limestone (a shift away from mud-brick).

- Symbolism: It represented a giant stairway for the King to climb toward the stars.

3. The Experimental Phase: The Trials of Sneferu

The transition from a “stepped” pyramid to a “true” smooth-sided pyramid was not a smooth process. Pharaoh Sneferu, the founder of the 4th Dynasty, was the most prolific builder in history, commissioned three massive pyramids:

A. The Meidum Pyramid

Originally intended to be a step pyramid, builders tried to encase it in limestone to create smooth sides. However, the outer casing lacked a firm foundation and eventually collapsed, leaving a tower-like core that stands in the desert today.

B. The Bent Pyramid at Dahshur

Learning from Meidum, builders started at a steep angle of $54^{\circ}$. However, as the structure grew, it became unstable. In a moment of ancient “emergency engineering,” they changed the angle to $43^{\circ}$ halfway up. This resulted in the famous “bent” silhouette.

C. The Red Pyramid

This was Sneferu’s final victory. Using a consistent $43^{\circ}$ angle from the base up, it became the world’s first successful smooth-sided pyramid. Its reddish hue comes from the inner limestone exposed after the white outer casing was stripped away.

4. The Zenith: The Giza Plateau (c. 2550–2490 BCE)

The 4th Dynasty reached its peak with Sneferu’s successors. They chose the Giza Plateau for its solid limestone bedrock, capable of supporting immense weight.

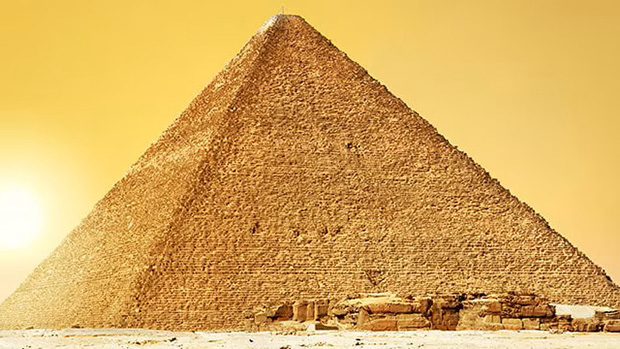

The Great Pyramid of Khufu

As the largest pyramid ever built, Khufu’s monument originally stood at 146.5 meters.

- Precision: The base is level to within 15 millimeters.

- Composition: It consists of roughly 2.3 million stone blocks, some weighing up to 80 tons.

- Mathematics: The ratio of the perimeter to the height is nearly equal to $2\pi$, suggesting an advanced understanding of geometry.

Khafre and Menkaure

Khufu’s son, Khafre, built his pyramid slightly smaller but on higher ground to appear taller. He also commissioned the Great Sphinx to guard the complex. Menkaure, the next successor, built a much smaller pyramid, signaling a shift in the kingdom’s resources.

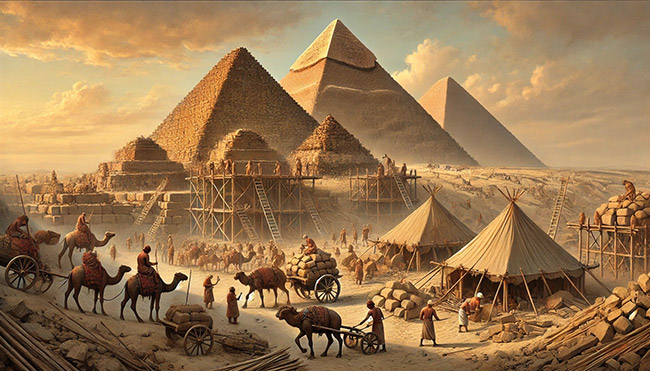

5. Life of the Builders: De-bunking the Slave Myth

A common misconception, popularized by Hollywood and early historians, is that the pyramids were built by slaves. Archaeological excavations of the “Builders’ Village” at Giza have proven otherwise.

- The Workforce: They were skilled Egyptian laborers and seasonal farmers.

- The Reward: Workers were paid in bread, beer, and tax breaks. They were treated with respect, and those who died on-site were given honorable burials near the pharaoh.

- Organization: The workforce was divided into “gangs” with names like “The Friends of Khufu,” fostering a sense of national pride and competition.

6. The Logistics: How Were They Built?

While we don’t have a preserved manual, several theories explain the construction:

- The Ramp Theory: Builders likely used a system of internal or external ramps made of mud-brick and rubble, lubricated with water to slide the heavy sleds.

- Quarrying: Copper chisels and wooden wedges were used to extract limestone from nearby quarries.

- Alignment: The pyramids are aligned almost perfectly to true north, likely achieved by observing the circumpolar stars.

7. The Decline and the Middle Kingdom

As the Old Kingdom collapsed due to drought and economic strain, the “Pyramid Age” began to fade. During the Middle Kingdom (c. 2040–1782 BCE), pharaohs like Senusret III continued building pyramids, but with a fatal flaw: they used mud-brick cores with stone casings.

When the outer stone was stolen for other buildings in later centuries, the mud-brick cores eroded in the rain, leaving behind the “crumpled” mounds we see at sites like Dahshur today.

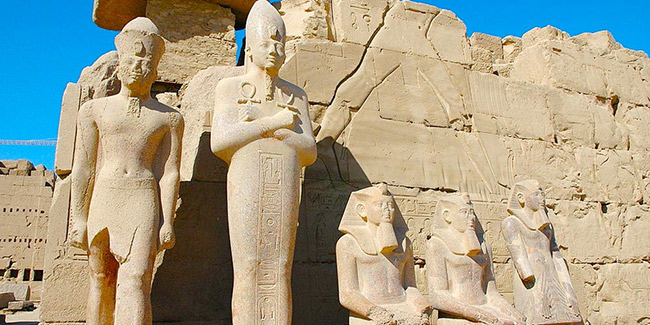

8. The End of an Era: The Valley of the Kings

By the New Kingdom (c. 1550 BCE), the pharaohs realized that giant pyramids were essentially “billboards for tomb robbers.” To protect their treasures and mummies, they abandoned pyramids in favor of rock-cut tombs hidden in the desolate Valley of the Kings near Luxor. The pyramid shape survived only as small pyramidions on top of private chapels.

9. The Legacy Beyond Egypt: Sudan and Mesoamerica

The influence of pyramid building didn’t stop at the Egyptian border.

- Nubian Pyramids: In modern-day Sudan, the Kingdom of Kush built hundreds of steep-sided pyramids for their royalty long after Egypt stopped.

- The Americas: Civilizations like the Maya and Aztecs built stepped pyramids (e.g., Chichen Itza) which, unlike Egyptian pyramids, were primarily temples with stairs leading to a top altar.

Key Data Summary Table

| Pyramid | Pharaoh | Dynasty | Est. Blocks |

| Step Pyramid | Djoser | 3rd | N/A (Stone/Brick mix) |

| Red Pyramid | Sneferu | 4th | ~1.5 Million |

| Great Pyramid | Khufu | 4th | ~2.3 Million |

| Khafre’s Pyramid | Khafre | 4th | ~2.1 Million |

Why the Pyramid Matters Today

The pyramids of Egypt stand as a testament to what human organization can achieve without modern machinery. They represent the transition of humanity from tribal groups to a unified state capable of massive logistical feats. They remain symbols of our desire to leave a mark on the world that outlasts time itself.

The history of pyramid building is far more than a timeline of construction; it is a testament to the relentless human pursuit of perfection and the afterlife. From the experimental “bent” walls of Sneferu to the mathematical precision of the Giza plateau, these structures mirror the rise and eventual transformation of Egyptian society.

They prove that with shared vision and sophisticated organization, a civilization can turn simple stone into an eternal legacy that defies the elements. While the era of pyramid building eventually ended, the monuments remain as silent teachers of engineering, resilience, and art.

Today, they stand not just as tombs for fallen kings, but as the ultimate symbol of humanity’s desire to reach for the heavens.

References

Lehner, Mark. The Complete Pyramids

National Geographic & Smithsonian Magazine Archive

Hawass, Zahi. Mountains of the Pharaohs: The Untold Story of the Pyramid Builders.

Verner, Miroslav. The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt’s Great Monuments.